The CurrentArundhati Roy: My mother and I were like two nuclear powers

In her new book, the acclaimed author Arundhati Roy grapples with her complex relationship with her late mother, Mary Roy, a woman who she says "raged against the idea of motherhood."

"She told me many times that she had tried her best to abort me because she didn't want another child," Arundhati told The Current's Matt Galloway.

"Of course as an adult now, I can sort of understand that she felt so trapped and awful."

Mary Roy died in 2022, at age 88. She was a celebrated educator and women's rights activist in India, who won a landmark legal case around women's inheritance rights in the 1980s. But her early years as a mother were marked with struggle. She was a single parent to Arundhati and her older brother, Lalit Kumar Christopher Roy, who were the frequent subject of their mother's rages and criticism.

The Booker Prize-winning author chronicles their tumultuous relationship in her new memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me. She remembers once invoking her mother's ire by comparing her to her sister, Arundhati's aunt, a woman who had a "perfect marriage and perfect children" and a seemingly perfect life.

My mother just turned on me in a rage and mimicked my baby-way of speaking- Arundhati Roy"I asked my mother, how are you both sisters? Because your older sister is so much thinner than you," she told Galloway.

Mary was on asthma medication that affected her weight, but Arundhati — who was six years old at the time — asked the question out of a child's curiosity, not as a form of judgment.

"My mother just turned on me in a rage and mimicked my baby-way of speaking," she said.

For that little girl, it felt like her mother had "cut me out of a picture book and torn me up, and I just sort of swirled away like water down a sink and disappeared," she said.

"But then immediately … she turns around and says, 'I'm your mother and your father and I love you double,'" Arundhati remembers.

While that ambiguity between her mother's love and cruelty is "always there," Arundhati said she understands where the anger came from — and credits her mother with helping her become the acclaimed writer she is today.

In the book, she writes that Mary's death left her "wrecked, heart-smashed … and more than a little ashamed by the intensity of my response."

"I know that she was just a damaged person who could not express love even if she felt it. And sometimes it came out very destructively," she told Galloway.

Arundhati Roy, her brother Lalit Kumar Christopher Roy and their mother, Mary Roy, in the India town of Ooty, in the state of Tamil Nadu, circa 1963. (Simon & Schuster Canada)'Headstrong, combative spirit'

Arundhati Roy, her brother Lalit Kumar Christopher Roy and their mother, Mary Roy, in the India town of Ooty, in the state of Tamil Nadu, circa 1963. (Simon & Schuster Canada)'Headstrong, combative spirit'Mary was born into a small community in Aymanam, a village in Kerala, southern India. She earned a degree in education and married the first man who asked her as a way "to get away from her very cruel father," Arundhati said.

The marriage took her more than 2,300 kilometres away to Bengal, at the western reach of the subcontinent, where she gave birth to two children. But upon realizing that her husband had an alcohol problem, she left with the children, in poor health and with little money.

With Arundhati's grandfather now dead, Mary moved the children into a small cottage that had belonged to him in Ooty, a small town in Tamil Nadu, the state neighbouring Kerala. But they were ousted by her brother and mother, under the auspices of the Travancore Christian Succession Act. This local law stipulated male heirs were entitled to the lion's share of any inheritance, granting women in the family only a tiny fraction.

Now in her 30s, Mary was humiliated and "a completely broken person," Arundhati said. But she set about opening up a school in the Kerala city of Kottayam, at first holding classes in the rented rooms of a rotary club.

"Gradually it became a very successful enterprise and she raised money, bought a little land and began to build this campus of her own," Arundhati said.

"She had a sort of headstrong, combative spirit, which was pretty amazing."

Once established, she used her resources to challenge the Travancore Christian Succession Act, winning equal inheritance rights for women from India's Supreme Court in 1986. The victory cemented Roy's legacy as a social reformer and women's rights activist.

By then, Arundhati was in her mid-20s. She had left home at 16 and largely stopped returning home or taking money from her mother by 18.

"All the humiliation that she suffered, she downloaded on to me and my brother," she said.

"Yet even as a young child I could see the process of where that anger came from … [so] I was also protective of her."

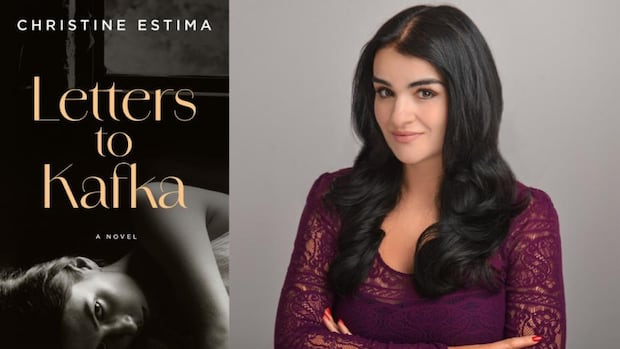

Arundhati Roy explores her relationship with her mother in a new memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me (Simon & Schuster Canada)'Two nuclear powers'

Arundhati Roy explores her relationship with her mother in a new memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me (Simon & Schuster Canada)'Two nuclear powers'Arundhati credits her mother with introducing her to reading and literature, and encouraging her to write about her own life and thoughts, even from a young age.

She once had a teacher, a missionary called Miss Mitten, who disliked Arundhati and told the little girl she could see Satan in her eyes. One evening, Mary asked Arundhati to write about what had happened in class that day.

"I wrote, 'I hate Miss Mitten and whenever I see her, I see rags and I think her knickers are torn,'" Arundhati recalled.

"That was, I think, my first essay …. My mother taught me how to sort of let the blood flow in my veins by writing about what happened."

She decided to write this memoir about her mother, both the good and bad, because she felt she couldn't keep her to herself.

"Despite everything that happened, she's one of the most remarkable women that I know," she said.

Arundhati said that they reconnected as adults, and reformed their relationship as equals.

"For a long time, the tension between us was that she knew that if anyone could stand up to her or put her down, it was me," Arundhati said.

For her part, Arundhati said she knew she would never do that because she loved and respected her mother too much.

"It was the very respectful relationship of two nuclear powers," she said.