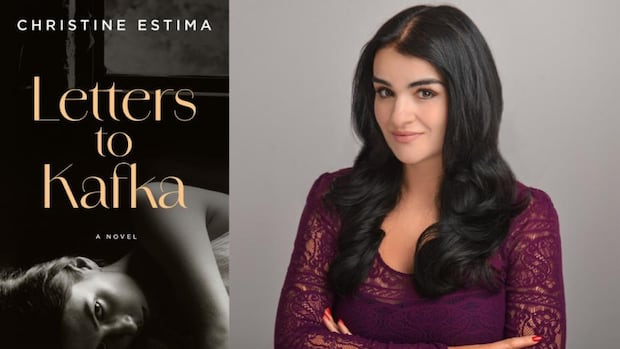

Bookends with Mattea RoachWho was the woman Kafka loved?

Twelve years ago, Canadian writer Christine Estima was broke and living in England, when she came across a journalism fellowship named for Milena Jesenská.

Estima had never heard of her before, so she started digging — and learned that Jesenská was a courageous journalist, translator and resister of the Nazi regime.

In history, however, Jesenská is most often remembered as Franz Kafka's lover.

She translated his work from German to Czech, starting a passionate correspondence that eventually led to an affair.

And while Kafka's letters to Jesenská are immortalized in the book Letters to Milena, her responses have never been found.

"I wanted her to not be known as Kafka's lover," said Estima on Bookends with Mattea Roach. "I wanted him to be known as hers."

That desire sparked Estima's debut novel, Letters to Kafka, which shares Jesenská's story and gives voice to a woman often overshadowed in history.

Estima also wrote the short story collection The Syrian Ladies Benevolent Society. She was longlisted for the CBC Short Story Prize in 2015.

The Toronto author joined Roach on Bookends to discuss the power of women writers and serendipitous moments she had during her research.

Mattea Roach: What was it about Milena Jesenská's story in particular that you found so compelling to turn into a novel?

Christine Estima: One of the major things was that she existed during a time where to be a woman who was also making her living as a writer was so ostentatious and so unexpected.

She's a Czech woman, married, living in Vienna at the end of the Great War. If you didn't die in the Great War, then the Spanish flu epidemic finished you off. The Austrian-Hungarian Empire has collapsed. There's fuel shortages and coal shortages and bread lines and inflation is through the roof.

Men are coming back from the front with hastily patched up faces and phantom limbs and respectable women are selling their bodies on the street to support their families. And Milena is like, "You know what? I'm going to be an author." It takes so much character and so much moxie.

Czech journalist, writer, editor and translator Milena Jesenská in 1915. (ALAMY/ARCHIVIO GBB)

Czech journalist, writer, editor and translator Milena Jesenská in 1915. (ALAMY/ARCHIVIO GBB)In your novel, we see the first time Jesenská and Kafka meet is this chance encounter at a cafe in Prague. There's this immediate mutual attraction. What transpires between them and what do you think drew them together?

I think that Milena viewed herself in a way that wasn't represented in her status in society. She came from a really well to do family in Prague. Her father ran an oral surgery and when she decided to get married, it was against her father's wishes because she married a Jewish man and so she had to run to Vienna.

But while she had been living in Prague, she had rubbed elbows with the intelligentsia and the literate social circles of Czech society and Bohemian society at the time.

When she moved to Vienna, she was broke. Her husband didn't really share his wages with her, and so she had to port luggage at the train station just to make ends meet. She was incredibly intellectual, though. Her aunt had also been a writer for Czech newspapers and magazines.

So I think she felt like, "I don't deserve to be working here at this train station. I deserve to express my thoughts and my feelings and my intelligence in the written word."

So when she's in Prague and she's at Cafe Arco, which was a famous cafe in the centre of Prague where all the Czech intelligentsia used to hang out, and she runs into him, I think that felt like where she's supposed to be. Kafka, at this point, he's not the famous name that we know now, but he is well known within Czech and German circles at this point. He's well read enough and so that kind of felt like a meeting of minds.

It was, "Okay, I've met my match, I've met my intellectual equal." Through that it also sparked what turned out to be an erotic and sexual attraction.

Portrait of Austrian-born writer Franz Kafka. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Portrait of Austrian-born writer Franz Kafka. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)You spent four years researching the novel before you even began writing, which included a lot of trips to Vienna and Prague to be in the places that Milena lived. Can you talk a bit about that process?

I scoured through census records and voter rolls and declassified military files. I interviewed one of her biographers. I took notes at all of the museums. I had to become basically a scholar about the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia and also who was in charge of that. There were a lot of visits to concentration camps.

I discovered some things in situ that weren't in any text I came across. The biggest thing was that when Milena was arrested by the Gestapo in 1939, she was arrested at her last address which was literally a mere four minute walk from Kafka's grave.

He had been dead for 15 years by the time she was arrested. So when I realized, walking down that street, that he's buried right there I was like that had to be a choice. She could have lived anywhere in Prague. This was kind of on the outskirts of Prague, so why else would she choose to live near the new Jewish cemetery?

I know you also travelled back to Vienna for about a month during the process of writing the manuscript and found a similar, serendipitous connection between yourself and Milena. Can you talk about that story and what that discovery felt like?

When I found out that there was a month-long opportunity to house sit in the heart of Vienna, I jumped at it. The house was located on a street called Lerchenfelder Straße and Milena and her first husband, Ernst Pollack, lived on the same street. But it's a really long street, so I didn't actually think much about it.

But when I arrived at the house, I was literally across the street from that apartment that she lived in when she was corresponding with Kafka. I was super excited.

While I was there, I was also looking after this dog. So every time I would take the dog for a walk, I would walk by Milena's apartment and I'd be like, "Hi, Milena."

Then, one time, I was walking by and the front door to the apartment block where she lived was open. And I scooped up the puppy dog and I'm like, "We're going in."

Obviously I wasn't able to enter her apartment, but in the book, I describe her going up and down the stairwell. I'm able to describe it because I was in that stairwell. I know what it looked like. And it was just such a joy to be walking her street and to see her neighborhood.

It was just so exciting, and I think that that excitement about that moment in time informed the work.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. It was produced by Katy Swailes.