BBC News

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn late 2023, sisters Lisa and Nicole were told they had inherited a substantial sum from their late Aunt Christine. But while they were absorbing this life-changing news, the windfall was just as quickly snatched away.

A man unknown to Christine's family, friends or neighbours, appeared - apparently from nowhere - and produced a will, naming him sole heir to her entire estate.

Doubts about the man's claim grew as troubling details emerged. However, the police and probate service said they would not investigate.

Lisa and Nicole's is one of several similar cases investigated by BBC News in the south of England.

We found mounting evidence that a criminal gang has been carrying out systematic will fraud by exploiting weaknesses in the probate system, stealing millions of pounds from the estates of dead people, and committing serious tax fraud.

'My dear friend'

Lisa and Nicole were upset to hear about the death of their aunt, Christine Harverson, whom they had not seen since their early childhood. They were also shocked to be told that they stood to inherit her entire estate, including a house in Wimbledon, south London, which could be worth nearly £1m. She had not left a will, and they were her closest living relatives.

The sisters were alerted to their inheritance by an "heir-finder" company, Anglia Research Services. Heir-finders use an official government register that lists estates where no will has been made. They research the dead person's family in order to identify, locate and contact the rightful heirs.

In return for a portion of the inheritance, these companies act on the heirs' behalf and apply for what's known as a grant of probate. This gives them the legal right to deal with a deceased person's estate – in other words, their property, money and possessions.

However, on this occasion, the application for probate on behalf of Lisa and Nicole was stopped in its tracks.

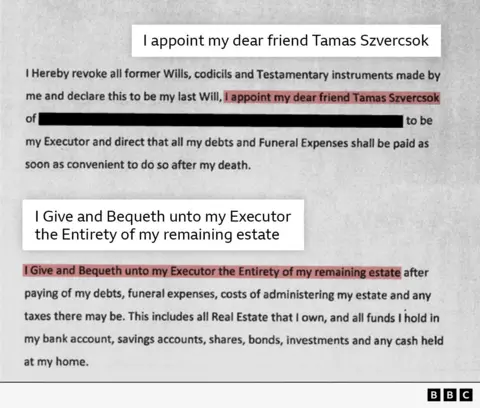

A Hungarian man by the name of Tamas Szvercsok contacted the probate service, and produced a will describing him as Christine's "dear friend".

It named him the beneficiary of her entire estate, as well as sole executor - the person legally responsible for carrying out the instructions in the will.

The possibility that Mr Szvercsok was genuine, initially was not dismissed out of hand.

"It happens - sometimes cases slip through the net and a will is unearthed," says Matt Boardman, a former police officer who works for Anglia Research.

However, there were clear signs something was amiss:

Christine's neighbour and friend, Sue, said she had never mentioned a Hungarian friend at any point in the years they had known each otherThe will was dated 2016 - Christine was housebound and disabled by this time, and receiving practically no visitorsThe terms of the will meant that Christine would have disinherited her husband and carer Dennis, who in 2016 was still alive (he died in 2020)Moreover, because Dennis was the joint owner of their house, Christine could not have legally bequeathed the house without his consentAfter Dennis's death, Christine entered a care home, but there was no record of Mr Szvercsok ever visiting her Joe Dixey/BBC

Joe Dixey/BBCSue (pictured in front of Christine Harverson's house) cast doubt on the authenticity of her late neighbour's will

Other even more troubling details stood out.

Christine's home address was misspelled on the will, and even though it was dated 2016, the address given for Mr Szvercsok was a block of flats that had not been built until 2021.

Matt Boardman contacted Mr Szvercsok, who replied by email: "I never heard of any family. I'm the sole executor of her will."

Despite presenting what they thought was a strong case to police and the probate service, Lisa and Nicole were told they would have to bring a civil action if they wanted to prove that the will was a fake. That would cost tens of thousands of pounds which they do not have.

Lisa now says she sometimes wishes she had never been told about the will in the first place: "All it's done is bring misery really, and heartache. It's just a whole nightmare."

'Vacant goods'

Stealing a dead person's property and financial assets appears to be extremely easy under UK law, if no will can be located.

The official government register of unclaimed estates (in England and Wales?) is called Bona Vacantia (Latin for "vacant goods"), and is freely accessible online. It currently contains about 6,000 names and is updated daily.

Legitimate heir-hunting companies use Bona Vacantia to research potential clients, but it also appears to have become a valuable resource for criminals.

To claim an estate where there is no known heir, a fraudster simply has to find a promising name on Bona Vacantia, produce a will quickly enough, and be awarded grant of probate.

Since 2017 it's been possible to apply for grant of probate online, but critics of the system say it is failing to detect suspicious applicants, and it also appears to increase the opportunity for tax fraud.

When someone dies, their estate has to be assessed for inheritance tax. This is not payable on estates worth £325,000 or less, but any amount over that threshold – with some exceptions - is taxed at 40%.

It's the responsibility of the person awarded grant of probate to make sure inheritance tax has been paid.

Applicants for grant of probate must complete a form to say this has been done, but under the current arrangements, they need do no more than declare on the online form that no tax is due.

It is a system that relies largely on trust, but gives ample opportunity for that trust to be roundly abused.

During our investigations we have come across cases where estates have been valued at just under the inheritance tax threshold, even though they include property worth far more.

One of these was the estate of Charles Haxton.

Whose house?

At the time of his death in 2021, Charles Haxton was living alone in a terraced house in Tooting, south London.

He was reclusive and only occasionally spoke to neighbours, although one of them, Roye Chapman, was there for him near the end when he suffered a bad fall outside.

"I rang the police and then got him up and got him into the ambulance," he says. "His head was all cut open, and then two weeks later, he died."

No will was initially found for Mr Haxton, and his name and address appeared on Bona Vacantia. This prompted Anglia Research to look for possible heirs, and they told several of his cousins that they could be in line to inherit Mr Haxton's estate.

Joe Dixey/BBC

Joe Dixey/BBCRoye Chapman stands in front of the house of his late neighbour, Charles Haxton

Then, as with Lisa and Nicole, the cousins were told that a will had appeared after all, leaving everything to one man - also Hungarian - called Roland Silye.

The family initially accepted his claim, to have been an old friend of Mr Haxton, but one relation, Barry, obtained a copy of the will and was struck by how odd it looked.

It left Mr Silye two properties - not only Mr Haxton's home in London, but also a house in Hertfordshire.

Together, the two properties would have been worth about £2m. However, Mr Silye listed the value of the estate as £320,500 – just £4,500 short of the amount at which inheritance tax kicked in.

What was even stranger was that Mr Haxton had never owned, and had no connection to, any house in Hertfordshire.

We visited this property. It was large and dilapidated, and neighbours told us it had been unoccupied for a long time.

The puzzle of the extra house also caught the attention of Neil Fraser, a partner in another heir-hunting company. He thinks that Mr Silye may have bundled the Hertfordshire property into a will in an attempt to fake ownership.

"He must have gone past that house and thought, 'I'll just take that derelict house. How can I get that house? Well, I can put it inside a will!"

Crucially, the will was accepted by the probate service, who did not check or raise any questions about the Hertfordshire house.

We were unable to trace Roland Silye in our investigation, and his motivation remains a mystery.

The will would not give him possession of the Hertfordshire house - the property registry and the electoral roll name the owner as a woman who would be in her 70s.

However, Mr Fraser speculates that the will could be used in future as leverage to take ownership when the real owner dies.

Despite reporting his suspicions to the police and the probate service, he says action was not taken.

Mr Silye cleared probate not only for Mr Haxton's estate, but also that of George Woon, an elderly man from Southall, west London.

Mr Woon also died in 2021, and shortly afterwards, his name appeared on Bona Vacantia. Mr Silye came forward with a will which named him as sole heir. Mr Woon's house was later sold at auction for £360,000.

A complex web

We asked an expert in financial fraud, Graham Barrow, to check whether there could be any connection between Roland Silye and Tamas Szvercsok.

Both have names of Hungarian origin, and, according to Companies House, both appear to be directors in a complex and interlinked web of companies.

Mr Barrow established that the address Mr Szvercsok gave in Mrs Harverson's will was also used by Mr Silye for some of his companies.

What these companies do is unclear, although some have been struck off for fraudulent addresses, and others have been warned for failing to provide accounts.

The pattern - multiple businesses, related addresses, similar names - is one which often indicates a criminal network, says Mr Barrow.

He adds that owning multiple companies can allow criminals to disperse funds across different accounts and locations, and makes life more difficult for law enforcement.

Another Hungarian name featuring in this web of companies is Bela Kovacs, who, according to a will dated 2021, was heir to the entire estate of Michael Judd, from Pinner, west London.

Michael Judd's estate included his bungalow in Pinner, west London

According to his neighbours, Mr Judd was a multi-talented individual with a distinguished record in the security services. However, in his final years he had become something of a hoarder, seldom leaving his house.

One neighbour, Chris, told us he thought the will had sounded strange and not only because Mr Judd had never mentioned Bela Kovacs.

A few months before his death in 2024, Mr Judd told Chris he had made a will long ago, but the people named on it were all now dead. In any case, he added, he did not know where it was.

"I suppose I better try and dig it out some time," Chris remembers him saying.

He feels it's inconceivable that Mr Judd would have troubled himself with these decisions if he had made a will three years previously.

We tracked Mr Kovacs down to a luxury estate in the Watford area but he refused to talk to us.

Joined-up writing

Other factors seem to connect these cases.

The wills made out for Charles Haxton, George Woon and the others we have seen, appear to have been written by the same person, according to handwriting expert Christina Strang.

"The numbers two, four and seven are all written in the same way on several addresses," she says.

She also sees other similarities, such as the spacing of the letters in different signatures, and the positioning of the signatures on the line.

"It seems to be one person actually signing, forging all of these."

Handwriting expert Christina Strang says it seems one person signed all the wills

Ms Strang also thinks this same person may have also forged signatures for the witnesses named on the wills, none of whom, we found, were apparently known to the deceased, and some of whom might have been completely fictitious.

There are disturbing similarities in the way that properties were treated during and after the probate process:

Shortly after Mr Szvercsok made his initial claim on Mrs Harverson's estate, her nieces discovered her Wimbledon house had been ransackedA workman employed to empty Mr Judd's house told us he had been instructed to empty it quickly, even though this meant having to destroy what appeared to be valuable heirloomsAfter Mr Haxton's house was cleared, the windows and doors were blacked out, and the locks strengthened; a year later, it emerged that it was being used as a cannabis farm (a fact that only emerged when a rival gang tried to force entry and neighbours alerted the police) Joe Dixey/BBC

Joe Dixey/BBCCharles Haxton's neighbours, Delorie, Roye and Sharon (L-R), alerted police to strange goings-on at their late neighbour's house

A system in trouble

As a result of our investigation, bank accounts for dozens of companies connected to the suspected fraudsters, have been suspended.

In addition, HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) has told us it now wants to question Roland Silye about inheritance tax which he might owe on the estate of Charles Haxton.

Bela Kovacs was granted probate over the estate of Michael Judd, which was valued at £310,000 - just below the inheritance tax threshold. However, HMRC's interest was also piqued by this case, and it has now suspended a planned sale of Mr Judd's bungalow in Pinner.

Meanwhile, the dispute over Christine Harverson's estate means the probate process has been frozen, and it looks unlikely to be resolved soon. Tamas Szvercsok cannot take possession of her Wimbledon house, but Lisa and Nicole lack the funds to go to the civil court and prove his will is fake.

Probate for Christine Harverson's estate has been frozen because of the dispute between her nieces and Tamas Szvercsok

We wrote to Mr Szvercsok and Mr Silye at the addresses supplied with their probate applications, offering them a right of reply, but we did not hear back.

When we shared our findings with the Ministry of Justice, which is ultimately responsible for the probate system, it told us that it was "working with law enforcement to ensure criminals feel the full force of the law".

However, a different picture emerges from others who know the system.

"Because probate isn't high profile – it's not sort of, for want of a better word, politically sexy, it doesn't stay in the headlines," says former MP Sir Bob Neill, who until the 2024 general election was the chair of the House of Commons Justice Select Committee.

In 2023, the select committee launched an inquiry into the probate system, but it was cut short by the election.

Sir Bob believes an over-eagerness to cut costs by digitising the probate system, has produced weaknesses which fraudsters are now exploiting.

"When you had regional offices you had human awareness, contact and scrutiny that was better suited to pick up cases where things have gone wrong," he says. "A purely sort of automated system isn't really good at doing that."

Sir Bob Neill

He says the system introduced in 2017 was a cheap and quick fix. It lacks the sophistication, he says, of programs used by insurance companies to deal with fraud, which can detect patterns of suspicious behaviour.

His concerns are echoed by Anglia Research's investigator, Matt Boardman, who says that previously, executors of wills would have had to attend their local probate registry to swear an oath, which "would allow the registrar to evaluate every single case on its own merit".

He says the system's move online "completely eliminated" the chance to question the executor's demeanour or behaviour.

"Goodness knows just how many of these have already gone through and been processed by the probate registry," he says, "and how rich we're making these people."