BBC

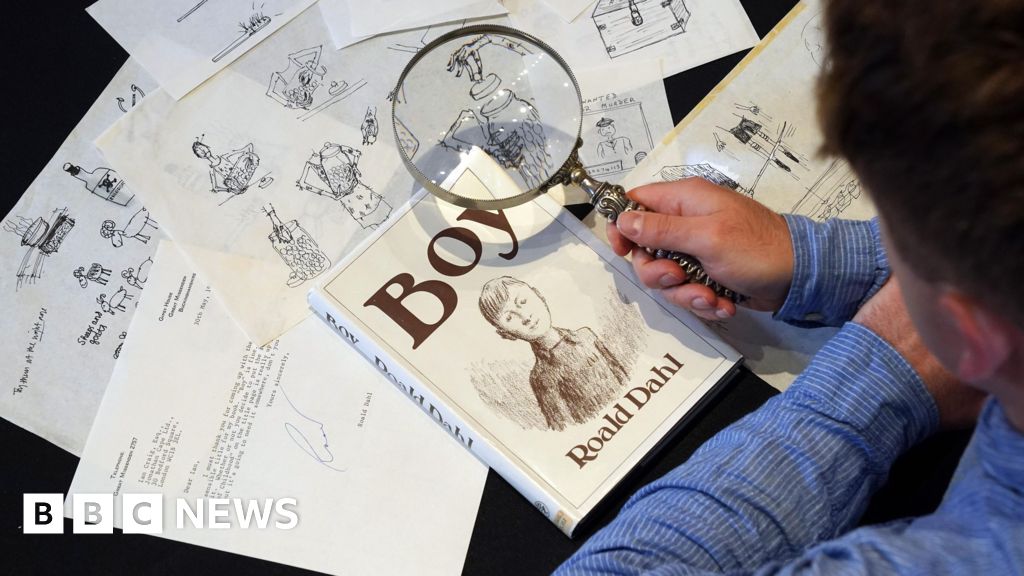

BBCJabez Petherick says hospice care made a big difference to him

As a nurse who supports terminally ill patients to die in their own homes, Angelina Blair sees first hand the last few hours of people's lives.

"There are times where you put on a brave face, you smile, you give the care that's right and when you leave the patient's home you go and talk to your colleagues or maybe shed a few tears," she says.

"Even if I've dealt with four deaths in a day, I've been able to have a family say that it was great, that mum, dad, sister was at home where they wanted to be."

She works for Rowcroft Hospice in Torquay, Devon, which supports 2,500 patients and their loved ones each year, most of whom choose to die in their own homes.

It is one of more than 200 hospices represented by the charity Hospice UK. These are at the centre of palliative (end-of-life) care in the country - and as a result, at the centre of the current debate over the assisted dying bill, too.

The bill would allow terminally ill adults with six months or less to live the right to medically end their lives in England and Wales. A key Commons vote is expected to take place this Friday which would determine whether the bill progresses to its next parliamentary stage.

Many in support of assisted dying say it would give terminal patients autonomy about how they die. But many of those opposed to it argue that policymakers should instead focus on improving palliative care, and some worry that patients undergoing end-of-life care would feel pressured to have an assisted death.

BBC News visited Rowcroft hospice to understand what staff think about that debate. We found uncertainty over how legalising assisted dying would affect their services, and concern about funding shortages.

"I feel very passionately about people having a choice about their life and what quality of life somebody lives with," Angelina says. "But being involved in actually administering medication that would end somebody's life knowingly, I don't know."

Angelina Blair is unsure about the proposals being debated

Hospices are not fully paid for by the government. Three quarters of Rowcroft's income comes from charity, such as fundraising events, legacies and donations from local people.

Rowcroft has only 12 inpatient beds as most of its patients opt to die at home, but other hospices have had to keep beds empty and lay off staff because of cost pressures.

Recent increases in employer national insurance contributions could hardly have come at a worse time, according to sector leaders.

And according to Hospice UK, the death rate in the UK is expected to increase over the next two decades, such that by 2040, about 130,000 more people in the UK are expected die each year than in 2023.

"I have no doubt, personally, if the [assisted dying] bill became law, that would be fully funded," says Rowcroft's chief executive Mark Hawkins.

"Shouldn't the government be funding palliative and end-of-life care now, to a greater extent, to ensure that we all have access to the best possible end-of-life and palliative care?"

The Department of Health says £100 million extra was provided to adult hospices in England this year for buildings and equipment and that the government is committed to ensuring every person has access to high quality and compassionate end-of-life care.

Jabez Petherick has incurable kidney cancer. He was transferred to Rowcroft after several weeks in hospital, during which he says he had dark and desperate times because of the pain. But he says hospice care has made a big difference.

"I used to go to bed, dread waking up, didn't want to wake up, I didn't want to wake up, because I knew the pain would start as soon as I woke up," he says. "And gradually it stopped. And I don't know how they did it but thank goodness they did."

The shifting views of patients in some cases is something which Jo Jacobs, a staff nurse, has noticed.

"I feel that it's very easy when patients first come in that they feel like they want to end their life, but they change their minds.

"And it's allowing patients to have that choice, but then also it could be quite scary that they've opted to end their life, but in a few weeks' time they're saying something completely, very different."

Respecting a patient's right to choose is all important, says Vicky Bartlett, the director of patient care at Rowcroft. "For my patients that I'm caring for, I want them to be able to make an informed choice," she says.

"And I want that choice to be around assisted dying, if that becomes law, but I also want that choice to be around palliative care."

Vicky Bartlett says an informed choice is key

Hospices have a lot to think about as the debate on the bill progresses.

Hospice UK has welcomed a new clause in the bill which requires the government to consult with palliative and end-of-life providers.

But its chief executive Toby Porter argues there is still a lot to consider. "It is inevitable that a change in the law would create many complex and often competing challenges," he says.

"But the precise nature of those challenges will not be apparent until there is clarity on where assisted dying would sit in the health and social care system, and the role hospices might be expected to play."

He says the bill has given no details on this and there has been no formal consultation with hospices.

Pain is a key symptom for many terminally ill patients and having the choice to free oneself from the extremes of it and have a dignified death is what drives many of those in support of assisted dying.

The message from Rowcroft is that if it is made legal they will have to weigh up a number of factors, including the views of the local community and staff, before deciding whether to provide that option to patients.

Since recording our interview Jabez has sadly died. He and his family granted the BBC permission to use his words after his death, to pay tribute to the staff at Rowcroft.

Family handout

Family handout